Égypte ancienne momies funérailles amulettes dieux rituels tombes cercueils officiel livre des morts

Égypte ancienne momies funérailles amulettes dieux rituels tombes cercueils officiel livre des morts, Égypte ancienne momies funérailles amulettes dieux rituels tombes cercueils livre des morts expédition

SKU: 827704

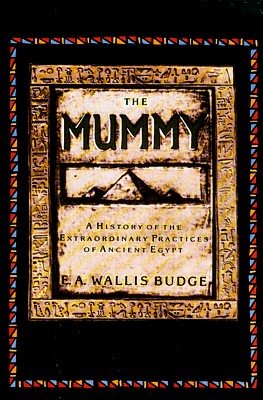

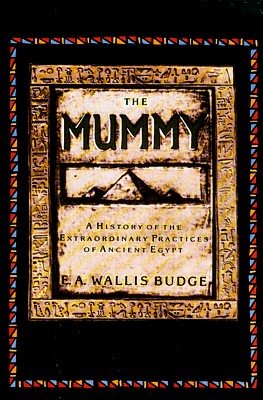

The Mummy: A History of the Extraordinary Practices of Ancient Egypt by E.A. Wallis Budge.

NOTE: We have 75,000 books in our library, almost 10,000 different titles. Odds are we have other copies of this same title in varying conditions, some less expensive, some better condition. We might also have different editions as well (some paperback, some hardcover, oftentimes international editions). If you don’t see what you want, please contact us and ask. We’re happy to send you a summary of the differing conditions and prices we may have for the same title.

DESCRIPTION: Hardcover with dustjacket: 404 pages. Publisher: Bell Publishing/Crown Publishing; (1989). Size: 9¼ x 6½ x 1¼ inches; 1¾ pounds. This fascinating, erudite, generously illustrated study offers comprehensive and meticulously detailed coverage of mummification processes, burial practices and goods, ritual texts, gods, graves, coffins, the Book of the Dead and much more. The preservation of the human body by embalming or mummification was the primary goal of every ancient Egyptian who wished to obtain eternal life. In "The Mummy", noted scholar and Egyptologist E. A. Wallis Budge presents a history of ancient Egypt and describes the infinite care, techniques, and heavy expense that went into mummifying a body. With this book he helps us to understand why, for the four thousand years that Egyptian civilization flourished, the mummy itself was considered the most important of objects.

The cult of mummification began when local authorities attempted to curb the then-widespread practice of cannibalism. The religious cult of Osiris offered reincarnation to the pure soul whose mortal remains were perfectly preserved and interred in secure and luxurious surroundings. Several thousand years later, an entire civilization had been built upon the mummy and its attendant trappings. Today we can see mummies on display in museums and now, through reading "The Mummy", we can understand the history and culture that led to their creation.

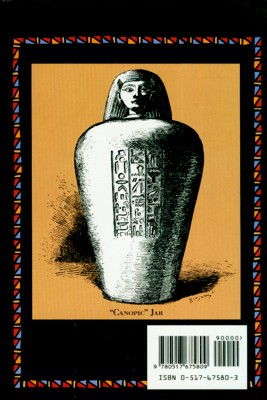

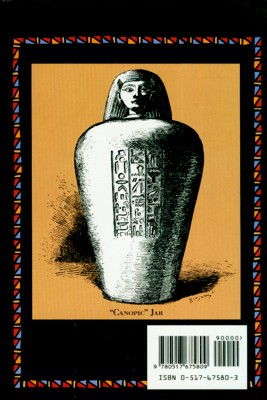

Budge covers Egyptian chronology and Dynasties; Egyptian history and language; the deciphering of the Rosetta Stone; and the subsequent unveiling of Egyptian literature. Also explored in detail are funeral rites; methods of mummification; mummy cloth and embroideries; the canopic jars used to store the sacred entrails of the dead, as well as the "Book of the Dead" itself. There are fascinating descriptions and illustrations of scarabs, amulets, and figures of the gods. Many animals sacred to the gods were also mummified. Among these were cats, crocodiles, hawks, and scorpions. From the mummification techniques used by the very wealthy to more middle class attempts at preservation in honey, to the lowly, desperate efforts of the poor to save their bodies with the use of bitumen and sand graves, this is the strange story of a civilization devoted to the cult of the dead.

CONDITION: NEW. New hardcover w/dustjacket. Bell Publishing/Crown Publishing (1989) 404 pages. Unblemished except for very faint edge and corner shelfwear to dustjacket and covers. Pages are pristine; clean, crisp, unmarked, unmutilated, tightly bound, unambiguously unread. Condition is entirely consistent with new stock from a bookstore environment wherein new books might show minor signs of shelfwear, consequence of simply being shelved and re-shelved. Satisfaction unconditionally guaranteed. In stock, ready to ship. No disappointments, no excuses. PROMPT SHIPPING! HEAVILY PADDED, DAMAGE-FREE PACKAGING! Meticulous and accurate descriptions! Selling rare and out-of-print ancient history books on-line since 1997. We accept returns for any reason within 30 days! #1759d.

PLEASE SEE IMAGES BELOW FOR SAMPLE PAGES FROM INSIDE OF BOOK.

PLEASE SEE PUBLISHER, PROFESSIONAL, AND READER REVIEWS BELOW.

PUBLISHER REVIEW:

REVIEW: To obtain eternal life the ancient Egyptians believed the body, upon death, had to undergo a mummification or embalming process. In "The Mummy" the noted Egyptologist Ernest A. Wallis Budge gives an account of the history of ancient Egypt and describes the techniques used in mummification and the rituals and artifacts associated with this funereal rite. To the ancient Egyptian, the embalming of a dead body acted as a barrier against decay and prepared it for the return of the soul (and thereafter everlasting life). As the author notes, great care was taken in the preparation of the tombs to repel attacks by demons. To ensure the mummy rested in comfort the tombs were decorated with familiar scenes and with everyday objects from the persons life. This fascinating volume will interest anyone wishing to understand not only the process of mummification, but also the cultural background of a ritual upon which an entire civilization was built.

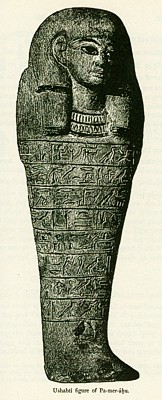

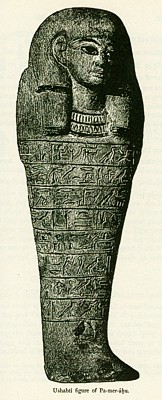

Major subject headings include: The Egyptian Race and Language; The Land of Egypt; Egyptian Chronology; The History of Egypt (Dynasties 1-30, Persian Rulers, Macedonian Rulers, The Ptolemies, The Romans, The Byzantines, The Muhammadans); List of Egyptian Dynasties and the Dates Assigned them by Egyptologists; List of Nomes of Upper and Lower Egypt; List of the Cartouches of the Principal Egyptian Kings; The Rosetta Stone; An Egyptian Funeral; Methods of Mummifying; Mummy Cloth and Embroideries; Canopic Jars; Chests for Canopic Jars; The Book of the Dead; Pillows; Ushabti Figures; Ptah-Seeker-Ausar Figures; Sepulchral Boxes; Funeral Cones; Stelae; Vases; Toiletry Objects; Necklaces, Rings and Bracelets; Scarabs; Amulets; Figures of Gods; Figures of Animals; Figures of Kings and Private Persons; Coffins; Sarcophagi; Egyptian Tombs; Egyptian Writing Materials; Egyptian Writing; Mummies of Animals, Reptiles, Birds, and Fishes; Cippi of Horus; The Egyptian Months; Egyptian and Coptic Numbers; A List of Common Hieroglyphic Characters; A List of Common Determinatives.

PROFESSIONAL REVIEWS:

REVIEW: The author explains both the process of mummification (dont try this at home) and the cultural background of a ritual on which a whole civilization was built. This noted Egyptologist gives an account of the history of ancient Egypt and describes the techniques used as well as the artifacts associated with this funereal rite. Illustrated with diagrams, hieroglyphs and facsimile drawings. Not a popular account, rather a scholarly examination, this is highly recommended for those who are serious enthusiasts or students of ancient Egypt.

REVIEW: In this book (originally published in 1893) noted Egyptologist Wallis Budge gives an account of the history of ancient Egypt and describes the techniques used in mummification, and the rituals and artifacts associated with the funeral rites. Not casual reading, but certainly worthwhile.

REVIEW: A history of ancient Egypt and their customs including mummification, funereal amulets and scarabs, idols and mummy making, and how to read hieroglyphics. A classic and quintessential reading.

READER REVIEWS:

REVIEW: This handbook is a good reference to keep on ones desk about ancient Egypt. Good overview of hieroglyphics, funeral practices and the fundamental tenets of Egyptian religion. Be warned that is not a "popular" history; its clearly aimed at the serious student. All in all, the results are well worth the readers effort.

REVIEW: Originally printed in 1893, this book still stands as one of the most concise explanatory introduction to the arid world of funerary Egyptian Archaeology. Although not "everything" is touched upon, there are so many detailed comments and references to writings so-long forgotten and missing, that this alone makes this tile a necessary one for any one interested in the subject-matter. It is true that there are more updated - and equally important - "hand-books" on the same (such as the one by Dr. J. Spencer, "Death in Ancient Egypt" - long out-of-print), but this one has what the others lack. Buy it, you will not repent.

REVIEW: Although weve learned a lot over the last century about life and culture in Ancient Egypt, this 1893 classic remains one of the best introductions to the field. Covering all the dynasties from Narmer through to the post-Cleopatra Roman occupation, this book contains enough detailed explanation to enable interested readers to teach themselves the basics of reading hieroglyphic inscriptions and wall texts. As fresh today as when it first appeared.

REVIEW: Although not a light or casual read, this book brings out some great points on the archeology of funerary in ancient Egypt. Beginning with a history of Egypt, to a concise history of hieroglyphs and the history of writing in Egypt, and then on to the meaty stuff of mummies and all the gory details. Budge concludes with a nice summary of major talismans and seals. Although this book is not a complete book in any right it is a good beginner book to read before delving into the macabre world of ancient Egypt.

ADDITIONAL BACKGROUND:

MUMMIFICATION IN ANCIENT EGYPT: The practice of mummifying the dead began in ancient Egypt circa 3500 B.C. The English word mummy comes from the Latin mumia which is derived from the Persian mum meaning wax and refers to an embalmed corpse which was wax-like. The idea of mummifying the dead may have been suggested by how well corpses were preserved in the arid sands of the country. Early graves of the Badarian Period (circa 5000 B.C.) contained food offerings and some grave goods, suggesting a belief in an afterlife, but the corpses were not mummified. These graves were shallow rectangles or ovals into which a corpse was placed on its left side, often in a fetal position. They were considered the final resting place for the deceased and were often, as in Mesopotamia, located in or close by a familys home.

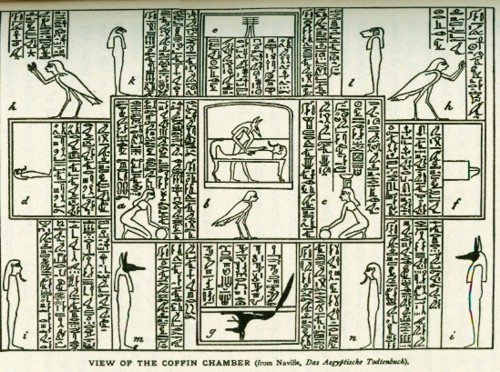

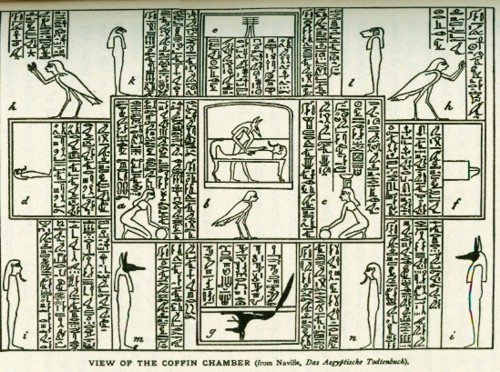

Graves evolved throughout the following eras until, by the time of the Early Dynastic Period in Egypt (circa 3150 - 2613 B.C.), the mastaba tomb had replaced the simple grave, and cemeteries became common. Mastabas were seen not as a final resting place but as an eternal home for the body. The tomb was now considered a place of transformation in which the soul would leave the body to go on to the afterlife. It was thought, however, that the body had to remain intact in order for the soul to continue its journey. Once freed from the body, the soul would need to orient itself by what was familiar. For this reason, tombs were painted with stories and spells from The Book of the Dead, to remind the soul of what was happening and what to expect, as well as with inscriptions known as The Pyramid Texts and Coffin Texts which would recount events from the dead persons life. Death was not the end of life to the Egyptians but simply a transition from one state to another. To this end, the body had to be carefully prepared in order to be recognizable to the soul upon its awakening in the tomb and also later.

By the time of the Old Kingdom of Egypt (circa 2613-2181 B.C.), mummification had become standard practice in handling the deceased and mortuary rituals grew up around death, dying, and mummification. These rituals and their symbols were largely derived from the cult of Osiris who had already become a popular god. Osiris and his sister-wife Isis were the mythical first rulers of Egypt, given the land shortly after the creation of the world. They ruled over a kingdom of peace and tranquility, teaching the people the arts of agriculture, civilization, and granting men and women equal rights to live together in balance and harmony.

Osiris brother, Set, grew jealous of his brothers power and success, however, and so murdered him; first by sealing him in a coffin and sending him down the Nile River and then by hacking his body into pieces and scattering them across Egypt. Isis retrieved Osiris parts, reassembled him, and then with the help of her sister Nephthys, brought him back to life. Osiris was incomplete, however - he was missing his penis which had been eaten by a fish - and so could no longer rule on earth. He descended to the underworld where he became Lord of the Dead. Prior to his departure, though, Isis had mated with him in the form of a kite and bore him a son, Horus, who would grow up to avenge his father, reclaim the kingdom, and again establish order and balance in the land.

This myth became so incredibly popular that it infused the culture and assimilated earlier gods and myths to create a central belief in a life after death and the possibility of resurrection of the dead. Osiris was often depicted as a mummified ruler and regularly represented with green or black skin symbolizing both death and resurrection. Egyptologist Margaret Bunson writes: "The cult of Osiris began to exert influence on the mortuary rituals and the ideals of contemplating death as a "gateway into eternity". This deity, having assumed the cultic powers and rituals of other gods of the necropolis, or cemetery sites, offered human beings salvation, resurrection, and eternal bliss."

Eternal life was only possible, though, if ones body remained intact. A persons name, their identity, represented their immortal soul, and this identity was linked to ones physical form. Parts of the Soul. The soul was thought to consist of nine separate parts: 1.The Khat was the physical body; 2.The Ka one’s double-form (astral self); 3.The Ba was a human-headed bird aspect which could speed between earth and the heavens (specifically between the afterlife and ones body); 4.The Shuyet was the shadow self; 5.The Akh was the immortal, transformed self after death; 6.The Sahu was an aspect of the Akh; 7.The Sechem was another aspect of the Akh; 8.The Ab was the heart, the source of good and evil, holder of ones character; 9.The Ren was one’s secret name.

The Khat needed to exist in order for the Ka and Ba to recognize itself and be able to function properly. Once released from the body, these different aspects would be confused and would at first need to center themselves by some familiar form. When a person died, they were brought to the embalmers who offered three types of service. According to Herodotus: "The best and most expensive kind is said to represent [Osiris], the next best is somewhat inferior and cheaper, while the third is cheapest of all". The grieving family was asked to choose which service they preferred, and their answer was extremely important not only for the deceased but for themselves. Burial practice and mortuary rituals in ancient Egypt were taken so seriously because of the belief that death was not the end of life.

Obviously, the best service was going to be the most expensive, but if the family could afford it and yet chose not to purchase it, they ran the risk of a haunting. The dead person would know they had been given a cheaper service than they deserved and would not be able to peacefully go on into the afterlife; instead, they would return to make their relatives lives miserable until the wrong was righted. Burial practice and mortuary rituals in ancient Egypt were taken so seriously because of the belief that death was not the end of life. The individual who had died could still see and hear, and if wronged, would be given leave by the gods for revenge.

It would seem, however, that people still chose the level of service they could most easily afford. Once chosen, that level determined the kind of coffin one would be buried in, the funerary rites available, and the treatment of the body. Egyptologist Salima Ikram, professor of Egyptology at the American University at Cairo, has studied mummification in depth and provides the following: "The key ingredient in the mummification was natron, or netjry, divine salt. It is a mixture of sodium bicarbonate, sodium carbonate, sodium sulphate and sodium chloride that occurs naturally in Egypt, most commonly in the Wadi Natrun some sixty four kilometres northwest of Cairo. It has desiccating and defatting properties and was the preferred desiccant, although common salt was also used in more economical burials." In the most expensive type of burial service, the body was laid out on a table and washed. The embalmers would then begin their work at the head: "The brain was removed via the nostrils with an iron hook, and what cannot be reached with the hook is washed out with drugs; next the flank is opened with a flint knife and the whole contents of the abdomen removed; the cavity is then thoroughly cleaned and washed out, firstly with palm wine and again with an infusion of ground spices. After that it is filled with pure myrrh, cassia, and every other aromatic substance, excepting frankincense, and sewn up again, after which the body is placed in natron, covered entirely over for seventy days – never longer. When this period is over, the body is washed and then wrapped from head to foot in linen cut into strips and smeared on the underside with gum, which is commonly used by the Egyptians instead of glue. In this condition the body is given back to the family who have a wooden case made, shaped like a human figure, into which it is put."

In the second-most expensive burial, less care was given to the body: "No incision is made and the intestines are not removed, but oil of cedar is injected with a syringe into the body through the anus which is afterwards stopped up to prevent the liquid from escaping. The body is then cured in natron for the prescribed number of days, on the last of which the oil is drained off. The effect is so powerful that as it leaves the body it brings with it the viscera in a liquid state and, as the flesh has been dissolved by the natron, nothing of the body is left but the skin and bones. After this treatment, it is returned to the family without further attention.

The third and cheapest method of embalming was "simply to wash out the intestines and keep the body for seventy days in natron". The internal organs were removed in order to help preserve the corpse, but because it was believed the deceased would still need them, the viscera were placed in canopic jars to be sealed in the tomb. Only the heart was left inside the body as it was thought to contain the Ab aspect of the soul. The embalmers removed the organs from the abdomen through a long incision cut into the left side. In removing the brain, as Ikram notes, they would insert a hooked surgical tool up through the dead persons nose and pull the brain out in pieces but there is also evidence of embalmers breaking the nose to enlarge the space to get the brain out more easily.

Breaking the nose was not the preferred method, though, because it could disfigure the face of the deceased and the primary goal of mummification was to keep the body intact and preserved as life-like as possible. This process was followed with animals as well as humans. Egyptians regularly mummified their pet cats, dogs, gazelles, fish, birds, baboons, and also the Apis bull, considered an incarnation of the divine. The removal of the organs and brain was all about drying out the body. The only organ they left in place, in most eras, was the heart because that was thought to be the seat of the persons identity and character. Blood was drained and organs removed to prevent decay, the body was again washed, and the dressing (linen wrapping) applied.

Although the above processes are the standard observed throughout most of Egypts history, there were deviations in some eras. Bunson notes: "Each period of ancient Egypt witnessed an alteration in the various organs preserved. The heart, for example, was preserved in some eras, and during the Ramessid dynasties the genitals were surgically removed and placed in a special casket in the shape of the god Osiris. This was performed, perhaps, in commemoration of the gods loss of his own genitals or as a mystical ceremony. Throughout the nations history, however, the canopic jars were under the protection of the Mesu Heru, the four sons of Horus. These jars and their contents, the organs soaked in resin, were stored near the sarcophagus in special containers."

Once the organs had been removed and the body washed, the corpse was wrapped in linen - either by the embalmers, if one had chosen the most expensive service (who would also include magical amulets and charms for protection in the wrapping), or by the family - and placed in a sarcophagus or simple coffin. The wrapping was known as the linen of yesterday because, initially, poor people would give their old clothing to the embalmers to wrap the corpse in. This practice eventually led to any linen cloth used in embalming known by the same name.

The funeral was a public affair at which, if one could afford them, women were hired as professional mourners. These women were known as the Kites of Nephthys and would encourage people to express their grief through their own cries and lamentation. They would reference the brevity of life and how suddenly death came but also gave assurance of the eternal aspect of the soul and the confidence that the deceased would pass through the trial of the weighing of the heart in the afterlife by Osiris to pass on to paradise in the Field of Reeds.

Grave goods, however rich or modest, would be placed in the tomb or grave. These would include shabti dolls who, in the afterlife, could be woken to life through a spell and assume the dead persons tasks. Since the afterlife was considered an eternal and perfect version of life on earth, it was thought there was work there just as in ones mortal life. The shabti would perform these tasks so the soul could relax and enjoy itself. Shabti dolls are important indicators to modern archaeologists on the wealth and status of the individual buried in a certain tomb; the more shabti dolls, the greater the wealth.

Besides the shabti, the person would be buried with items thought necessary in the afterlife: combs, jewelry, beer, bread, clothing, ones weapons, a favorite object, even ones pets. All of these would appear to the soul in the afterlife and they would be able to make use of them. Before the tomb was sealed, a ritual was enacted which was considered vital to the continuation of the souls journey: the Opening of the Mouth Ceremony. In this rite, a priest would invoke Isis and Nephthys (who had brought Osiris back to life) as he touched the mummy with different objects (adzes, chisels, knives) at various spots while anointing the body. In doing so, he restored the use of ears, eyes, mouth, and nose to the deceased.

The son and heir of the departed would often take the priests role, thus further linking the rite with the story of Horus and his father Osiris. The deceased would now be able to hear, see, and speak and was ready to continue the journey. The mummy would be enclosed in the sarcophagus or coffin, which would be buried in a grave or laid to rest in a tomb along with the grave goods, and the funeral would conclude. The living would then go back to their business, and the dead were then believed to go on to eternal life. [Ancient History Encyclopedia].

DEATH IN ANCIENT EGYPT: To the ancient Egyptians, death was not the end of life but only a transition to another plane of reality. Once the soul had successfully passed through judgment by the god Osiris, it went on to an eternal paradise, The Field of Reeds, where everything which had been lost at death was returned and one would truly live happily ever after. Even though the Egyptian view of the afterlife was the most comforting of any ancient civilization, people still feared death. Even in the periods of strong central government when the king and the priests held absolute power and their view of the paradise-after-death was widely accepted, people were still afraid to die.

The rituals concerning mourning the dead never dramatically changed in all of Egypts history and are very similar to how people react to death today. One might think that knowing their loved one was on a journey to eternal happiness, or living in paradise, would have made the ancient Egyptians feel more at peace with death, but this is clearly not so. Inscriptions mourning the death of a beloved wife or husband or child - or pet - all express the grief of loss, how they miss the one who has died, how they hope to see them again someday in paradise - but not expressing the wish to die and join them anytime soon. There are texts which express a wish to die, but this is to end the sufferings of ones present life, not to exchange ones mortal existence for the hope of eternal paradise.

The prevailing sentiment among the ancient Egyptians, in fact, is perfectly summed up by Hamlet in Shakespeares famous play: "The undiscovered country, from whose bourn/No traveler returns, puzzles the will/And makes us rather bear those ills we have/Than fly to others that we know not of". The Egyptians loved life, celebrated it throughout the year, and were in no hurry to leave it even for the kind of paradise their religion promised. A famous literary piece on this subject is known as Discourse Between a Man and his Ba (also translated as Discourse Between a Man and His Soul and The Man Who Was Weary of Life). This work, dated to the Middle Kingdom of Egypt (2040-1782 B.C.), is a dialogue between a depressed man who can find no joy in life and his soul which encourages him to try to enjoy himself and take things easier. The man, at a number of points, complains how he should just give up and die - but at no point does he seem to think he will find a better existence on the other side - he simply wants to end the misery he is feeling at the moment.

The dialogue is often characterized as the first written work debating the benefits of suicide, but scholar William Kelly Simpson disagrees, writing: "What is presented in this text is not a debate but a psychological picture of a man depressed by the evil of life to the point of feeling unable to arrive at any acceptance of the innate goodness of existence. His inner self is, as it were, unable to be integrated and at peace. His dilemma is presented in what appears to be a dramatic monologue which illustrates his sudden changes of mood, his wavering between hope and despair, and an almost heroic effort to find strength to cope with life. It is not so much life itself which wearies the speaker as it is his own efforts to arrive at a means of coping with lifes difficulties." As the speaker struggles to come to some kind of satisfactory conclusion, his soul attempts to guide him in the right direction of giving thanks for his life and embracing the good things the world has to offer. His soul encourages him to express gratitude for the good things he has in this life and to stop thinking about death because no good can come of it. To the ancient Egyptians, ingratitude was the gateway sin which let all other sins into ones life. To the ancient Egyptians, ingratitude was the gateway sin which let all other sins into ones life. If one were grateful, then one appreciated all that one had and gave thanks to the gods; if one allowed ones self to feel ungrateful, then this led one down a spiral into all the other sins of bitterness, depression, selfishness, pride, and negative thought.

The message of the soul to the man is similar to that of the speaker in the biblical book of Ecclesiastes when he says, "God is in heaven and thou upon the earth; therefore let thy words be few". The man, after wishing that death would take him, seems to consider the words of the soul seriously. Toward the end of the piece, the man says, "Surely he who is yonder will be a living god/Having purged away the evil which had afflicted him...Surely he who is yonder will be one who knows all things". The soul has the last word in the piece, assuring the man that death will come naturally in time and life should be embraced and loved in the present.

Another Middle Kingdom text, The Lay of the Harper, also resonates with the same theme. The Middle Kingdom is the period in Egyptian history when the vision of an eternal paradise after death was most seriously challenged in literary works. Although some have argued that this is due to a lingering cynicism following the chaos and cultural confusion of the First Intermediate Period, this claim is untenable. The First Intermediate Period of Egypt (2181-2040 B.C.) was simply an era lacking a strong central government, but this does not mean the civilization collapsed with the disintegration of the Old Kingdom, simply that the country experienced the natural changes in government and society which are a part of any living civilization.

The Lay of the Harper is even more closely comparable to Ecclesiastes in tone and expression as seen clearly in the refrain: "Enjoy pleasant times/And do not weary thereof/Behold, it is not given to any man to take his belongings with him/Behold, there is no one departed who will return again" (Simpson, 333). The claim that one cannot take ones possessions into death is a direct refutation of the tradition of burying the dead with grave goods: all those items one enjoyed and used in life which would be needed in the next world.

It is entirely possible, of course, that these views were simply literary devices to make a point that one should make the most of life instead of hoping for some eternal bliss beyond death. Still, the fact that these sentiments only find this kind of expression in the Middle Kingdom suggests a significant shift in cultural focus. The most likely cause of this is a more cosmopolitan upper class during this period, which was made possible precisely by the First Intermediate Period, which 19th- and 20th-century CE scholarship has done so much to vilify. The collapse of the Old Kingdom of Egypt empowered regional governors and led to greater freedom of expression from different areas of the country instead of conformity to a single vision of the king.

The cynicism and world-weary view of religion and the afterlife disappear after this period and New Kingdom (circa 1570-1069 B.C.) literature again focuses on an eternal paradise which waits beyond death. The popularity of The Book of Coming Forth by Day (better known as The Egyptian Book of the Dead) during this period is amongst the best evidence for this belief. The Book of the Dead is an instructional manual for the soul after death, a guide to the afterlife, which a soul would need in order to reach the Field of Reeds.

The reputation Ancient Egypt has acquired of being death-obsessed is actually undeserved; the culture was obsessed with living life to its fullest. The mortuary rituals so carefully observed were intended not to glorify death but to celebrate life and ensure it continued. The dead were buried with their possessions in magnificent tombs and with elaborate rituals because the soul would live forever once it has passed through deaths doors. While one lived, one was expected to make the most of the time and enjoy ones self as much as one could. A love song from the New Kingdom of Egypt, one of the so-called Songs of the Orchard, expresses the Egyptian view of life perfectly.

In the following lines, a sycamore tree in the orchard speaks to one of the young women who planted it when she was a little girl: "Give heed! Have them come bearing their equipment; Bringing every kind of beer, all sorts of bread in abundance; Vegetables, strong drink of yesterday and today; And all kinds of fruit for enjoyment; Come and pass the day in happiness; Tomorrow, and the day after tomorrow; Even for three days, sitting beneath my shade."

Although one does find expressions of resentment and unhappiness in life - as in the Discourse Between a Man and his Soul - Egyptians, for the most part, loved life and embraced it fully. They did not look forward to death or dying - even though promised the most ideal afterlife - because they felt they were already living in the most perfect of worlds. An eternal life was only worth imagining because of the joy the people found in their earthly existence. The ancient Egyptians cultivated a civilization which elevated each day to an experience in gratitude and divine transcendence and a life into an eternal journey of which ones time in the body was only a brief interlude. Far from looking forward to or hoping for death, the Egyptians fully embraced the time they knew on earth and mourned the passing of those who were no longer participants in the great festival of life. [Ancient History Encyclopedia].

THE SOUL IN ANCIENT EGYPT: At the beginning of time, the god Atum stood on the primordial mound in the midst of the waters of chaos and created the world. The power which enabled this act was heka (magic) personified in the god Heka, the invisible force behind the gods. The earth and everything in it was therefore imbued with magic, and this naturally included human beings. Humanity had been created by the gods, and one lived and moved owing to the magical force which animated them: the soul.

An individuals life on earth was considered only one part of an eternal journey. The personality was created at the moment of ones birth, but the soul was an immortal entity inhabiting a mortal vessel. When that vessel failed and the persons body died, the soul went on to another plane of existence where, if it was justified by the gods, it would live forever in a paradise which was a mirror image of ones earthly existence.

This soul was not only ones character, however, but a composite being of different entities, each of which had its own role to play in the journey of life and afterlife. The mortuary rituals which were such an important aspect of Egyptian culture were so carefully observed because each aspect of the soul had to be addressed in order for the person to continue on their way to eternity. The soul was thought to consist of nine separate parts which were integrated into a whole individual but had very distinct aspects.

Egyptologist Rosalie David explains: "The Egyptians believed that the human personality had many facets - a concept that was probably developed early in the Old Kingdom. In life, the preson was a complete entity, but if he had led a virtuous life, he could also have access to a multiplicity of forms that could be used in the next world. In some instances, these forms could be employed to help those whom the deceased wished to support or, alternately, to take revenge on his enemies.

In order for these aspects of the soul to function, the body had to remain intact, and this is why mummification became so integral a part of the mortuary rituals and the culture. In some eras, the soul was thought to be comprised of five parts and in others seven, but, generally, it was nine: "the soul was not only ones character but a composite being of different entities, each of which had its own role to play in the journey of life and afterlife."

The Khat was the physical body which, when it became a corpse, provided the link between ones soul and ones earthly life. The soul would need to be nourished after death just as it had to be while on earth, and so food and drink offerings were brought to the tomb and laid on an offerings table. Egyptologist Helen Strudwick observes that "one of the most common subjects for tomb paintings and carvings was the deceased seated at an offerings table laden with food". The dead body was not thought to actually eat this food but to absorb its nutrients supernaturally. Paintings and statues of the dead person were also placed in the tomb so that, if something should happen to damage the body, the statue or painting would assume its role.

The Ka was one’s double-form or astral self and corresponds to what most people in the present day consider a soul. This was "the vital source that enabled a person to continue to receive offerings in the next world". The ka was created at the moment of ones birth for the individual and so reflected ones personality, but the essence had always existed and was "passed across the successive generations, carrying the spiritual force of the first creation". The ka was not only ones personality but also a guide and protector, imbued with the spark of the divine. It was the ka which would absorb the power from the food offerings left in the tomb, and these would sustain it in the afterlife. All living things had a ka - from plants to animals and on up to the gods - which was evident in that they were, simply, alive.

The Ba is most often translated as soul and was a human-headed bird aspect which could speed between earth and the heavens and, specifically, between the afterlife and ones corpse. Each ba was linked to a particular body, and the ba would hover over the corpse after death but could also travel to the afterlife, visit with the gods, or return to earth to those places the person had loved in life. The corpse had to reunite with the ka each night in order for the ka to receive sustenance, and it was the job of the ba to accomplish this. The gods had a ba as well as a ka. Examples of this are the Apis bull which was the ba of Osiris and the Phoenix, the ba of Ra.

The Shuyet was the shadow self which means it was essentially the shadow of the soul. The shadow in Egypt represented comfort and protection, and the sacred sites at Amarna were known as Shadow of Ra for this reason. Exactly how the shuyet functioned is not clear, but it was considered extremely important and operated as a protective and guiding entity for the soul in the afterlife. The Egyptian Book of the Dead includes a spell where the soul claims, "My shadow will not be defeated" in stating its ability to traverse the afterlife toward paradise.

The Akh was the immortal, transformed, self which was a magical union of the ba and ka. Strudwick writes, "once the akh had been created by this union, it survived as an enlightened spirit, enduring and unchanged for eternity" (178). Akh is usually translated as spirit and was the higher form of the soul. Spell 474 of the Pyramid Texts states, "the akh belongs to heaven, the corpse to earth," and it was the akh which would enjoy eternity among the stars with the gods. The akh could return to earth, however, and it was an aspect of the akh which would come back as a ghost to haunt the living if some wrong had been done or would return in dreams to help someone they cared for.

The Sahu was the aspect of the Akh which would appear as a ghost or in dreams. It separated from the other aspects of the soul once the individual was justified by Osiris and judged worthy of eternal existence. The Sechem was another aspect of the Akh which allowed it mastery of circumstances. It was the vital life energy of the individual which manifested itself as the power to control ones surroundings and outcomes.

The Ab was the heart, the source of good and evil, which defined a persons character. This was the spiritual heart which rose from the physical heart (hat) which was left in the mummified body of the deceased for this reason: it was the seat of the persons individuality and the record of their thoughts and deeds during their time on earth. It was the ab which was weighed in the balances against the white feather of truth by Osiris and, if found heavier than the feather, it was dropped to the floor where it was devoured by the monster Amut. Once the heart was eaten, the soul ceased to exist. If the heart was found lighter than the feather, the soul was justified and could proceed on toward paradise. A special amulet was included in the mummification of the corpse and placed over the heart as a protective charm to prevent the heart from bearing witness against the soul and possibly condemning it falsely.

The Ren was one’s secret name. This was given to one at birth by the gods, and only the gods knew it. Scholar Nicholaus B. Pumphrey writes, "the only way that the fate or destiny can change is if a creature of higher power changes the name. As long as the name of the being exists, the being will exist throughout eternity as part of the fabric of the divine order" (6-7). The ren was the name by which the gods knew the individual soul and how one would be called in the afterlife.

The mortuary rituals were observed to address each aspect of the soul and assure the living that the deceased would live on after death. Mummification was practiced to preserve the body, amulets and magical texts were included to address the other spiritual facets which made up an individual. The dead were not forgotten once they were placed in their tomb. Rituals were then observed daily in their honor and for their continued existence. Rosalie David writes: "In order to ensure that the link was maintained between the living and the dead, so that the persons immortality was assured, all material needs had to be provided for the deceased, and the correct funerary rituals had to be performed. It was expected that a persons heir would bring the daily offerings to the tomb to sustain the owners ka."

If the family was unable to perform this duty, they could hire a Ka-servant who was a priest specially trained in the rituals. A tomb could not be neglected or else the persons spirit would suffer in the afterlife and could then return to seek revenge. This, in fact, is the plot of one of the best known Egyptian ghost stories, Khonsemhab and the Ghost, in which the spirit of Nebusemekh returns to ask help of Khonesmhab, the High Priest of Amun. Nebusemekhs tomb has been neglected to the point where no one even remembers where it is and no one comes to visit or bring the necessary offerings. Khonsemhab sends his servants to locate, repair, and refurbish the tomb and then promises to provide daily offerings to Nebusemekhs ka.

These offerings would be left on an altar table in the offering chapel of those tombs elaborate enough to have one or on the offerings table in the tomb. The ka of the deceased would enter the tomb through the false door provided and inhabit the body or a statue and draw nourishment from the offerings provided. In case there was a delay for whatever reason, a significant quantity of food and drink was buried with those who could afford it. Strudwick notes how "the immediate needs of the deceased were met by inhuming a veritable feast - meat, vegetables, fruit, bread, and jugs of wine, water, and beer - with the mummy" (186). This would ensure that the departed was provided for but did not negate the obligation on the part of the living to remember and care for the dead.

Offerings Lists, which stipulated what kinds of food were to be brought and in what quantity, were inscribed on tombs so that the Ka-servant or some other priest in the future could continue provisions, even long after the family was dead. Autobiographies accompanied the Offerings Lists to celebrate the persons life and provide a means of lasting remembrance. For the most part, people took the upkeep of their familys graves and the offerings seriously in honor of the departed and knowing that, someday, they would require the same kind of attention for the sustenance of their own souls. [Ancient History Encyclopedia].

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN MORTUARY RITUALS: Ever since European archaeologists began excavating in Egypt in the 18th and 19th centuries A.D., the ancient culture has been largely associated with death. Even into the mid-20th century CE reputable scholars were still writing on the death-obsessed Egyptians whose lives were lacking in play and without joy. Mummies in dark, labyrinthine tombs, strange rituals performed by dour priests, and the pyramid tombs of the kings remain the most prominent images of ancient Egypt in many peoples minds even in the present day, and an array of over 2,000 deities - many of them uniquely associated with the afterlife - simply seems to add to the established vision of the ancient Egyptians as obsessed with death. Actually, though, they were fully engaged in life, so much so that their afterlife was considered an eternal continuation of their time on earth.

When someone died in ancient Egypt the funeral was a public event which allowed the living to mourn the passing of a member of the community and enabled the deceased to move on from the earthly plane to the eternal. Although there were outpourings of grief and deep mourning over the loss of someone they loved, they did not believe the dead person had ceased to exist; they had merely left the earth for another realm. In order to make sure they reached their destination safely, the Egyptians developed elaborate mortuary rituals to preserve the body, free the soul, and send it on its way. These rituals encouraged the healthy expression of grief among the living but concluded with a feast celebrating the life of the deceased and his or her departure, emphasizing how death was not the end but only a continuation. Egyptologist Helen Strudwick notes, "for the life-loving Egyptians, the guarantee of continuing life in the netherworld was immensely important". The mortuary rituals provided the people with just that sort of guarantee.

The earliest burials in ancient Egypt were simple graves in which the deceased was placed, on the left side, accompanied by some grave goods. It is clear there was already a belief in some kind of afterlife prior to circa 3500 B.C. when mummification began to be practiced but no written record of what form this belief took. Simple graves in the Predynastic Period in Egypt (circa 6000 - 3150 B.C.) evolved into the mastaba tombs of the Early Dynastic Period (circa 3150 - 2613 B.C.) which then became the grand pyramids of the Old Kingdom (circa 2613-2181 B.C.). All of these periods believed in an afterlife and engaged in mortuary rituals, but those of the Old Kingdom are the best known from images on tombs. Although it is usually thought that everyone in Egypt was mummified after their death, the practice was expensive & only the upper class and nobility could afford it.

By the time of the Old Kingdom of Egypt, the culture had a clear understanding of how the universe worked and humanitys place in it. The gods had created the world and the people in it through the agency of magic (heka) and sustained it through magic as well. All the world was imbued with mystical life generated by the gods who would welcome the soul when it finally left the earth for the afterlife. In order for the soul to make this journey, the body it left behind needed to be carefully preserved, and this is why mummification became such an integral part of the mortuary rituals. Although it is usually thought that everyone in Egypt was mummified after their death, the practice was expensive, and usually only the upper class and nobility could afford it.

In the Old Kingdom the kings were buried in their pyramid tombs, but from the First Intermediate Period of Egypt (2181-2040 B.C.) onwards, kings and nobles favored tombs cut into rock face or into the earth. By the time of the New Kingdom (circa 1570-1069 B.C.) the tombs and the rituals leading to burial had reached their highest state of development. There were three methods of embalming/funerary ritual available: the most expensive and elaborate, a second, cheaper option which still allowed for much of the first, and a third which was even cheaper and afforded little of the attention to detail of the first. The following rituals and embalming methods described are those of the first, most elaborate option, which was performed for royalty and the specific rituals are those observed in the New Kingdom of Egypt.

After death, the body was brought to the embalmers where the priests washed and purified it. The mortuary priest then removed those organs which would decay most quickly and destroy the body. In early mummification, the organs of the abdomen and the brain were placed in canopic jars which were thought to be watched over by the guardian gods known as The Four Sons of Horus. In later times the organs were taken out, treated, wrapped, and placed back into the body, but canopic jars were still placed in tombs, and The Four Sons of Horus were still thought to keep watch over the organs.

The embalmers removed the organs from the abdomen through a long incision cut into the left side; for the brain, they would insert a hooked surgical tool up through the dead persons nose and pull the brain out in pieces. There is also evidence of embalmers breaking the nose to enlarge the space to get the brain out more easily. Breaking the nose was not the preferred method, though, because it could disfigure the face of the deceased and the primary goal of mummification was to keep the body intact and preserved as life-like as possible. The removal of the organs and brain was all about drying out the body - the only organ they left in place was the heart because that was thought to be the seat of the persons identity. This was all done because the soul needed to be freed from the body to continue on its eternal journey into the afterlife and, to do so, it needed to have an intact house to leave behind and also one it would recognize if it wished to return to visit.

After the removal of the organs, the body was soaked in natron for 70 days and then washed and purified again. It was then carefully wrapped in linen; a process which could take up to two weeks. Egyptologist Margaret Bunson explains: "This was an important aspect of the mortuary process, accompanied by incantations, hymns, and ritual ceremonies. In some instances the linens taken from shrines and temples were provided to the wealthy or aristocratic deceased in the belief that such materials had special graces and magical powers. An individual mummy would require approximately 445 square yards of material. Throughout the wrappings semiprecious stones and amulets were placed in strategic positions, each one guaranteed to protect a certain region of the human anatomy in the afterlife." Among the most important of these amulets was the one which was placed over the heart. This was done to prevent the heart from bearing witness against the deceased when the moment of judgment came. Since the heart was the seat of individual character, and since it was obvious that people often made statements they later regretted, it was considered important to have a charm to prevent that possibility. The embalmers would then return the mummy to the family who would have had a coffin or sarcophagus made. The corpse would not be placed in the coffin yet, however, but would be laid on a bier and then moved toward a waiting boat on the Nile River. This was the beginning of the funeral service which started in the early morning, usually departing either from a temple of the king or the embalmers center. The servants and poorer relations of the deceased were at the front of the procession carrying flowers and food offerings. They were followed by others carrying grave goods such as clothing and shabti dolls, favorite possessions of the deceased, and other objects which would be necessary in the afterlife.

Directly in front of the corpse would be professional mourners, women known as the Kites of Nephthys, whose purpose was to encourage others to express their grief. The kites would wail loudly, beat their breasts, strike their heads on the ground, and scream in pain. These women were dressed in the color of mourning and sorrow, a blue-gray, and covered their faces and hair with dust and earth. This was a paid position, and the wealthier the deceased, the more kites would be present in the procession. A scene from the tomb of the pharaoh Horemheb (1320-1292 B.C.) of the New Kingdom vividly depicts the Kites of Nephthys at work as they wail and fling themselves to the ground.

In the Early Dynastic Period in Egypt, the servants would have been killed upon reaching the tomb so that they could continue to serve the deceased in the afterlife. By the time of the New Kingdom, this practice had long been abandoned and an effigy now took the place of the servants known as a tekenu. Like the shabti dolls, which one would magically animate in the afterlife to perform work, the tekenu would later come to life, in the same way, to serve the soul in paradise.

The corpse and the tekenu were followed by priests, and when they reached the eastern bank of the Nile, the tekenu and the oxen who had pulled the corpse were ritually sacrificed and burned. The corpse was then placed on a mortuary boat along with two women who symbolized the goddesses Isis and Nephthys. This was in reference to the Osiris myth in which Osiris is killed by his brother Set and returned to life by his sister-wife Isis and her sister Nephthys. In life, the king was associated with the son of Osiris and Isis, Horus, but in death, with the Lord of the Dead, Osiris. The women would address the dead king as the goddesses speaking to Osiris.

The boat sailed from the east side (representing life) to the west (the land of the dead) where it docked and the body was then moved to another bier and transported to its tomb. A priest would have already arranged to have the coffin or sarcophagus set up at the entrance of the tomb, and at this point, the corpse was placed inside of it. The priest would then perform the Opening of the Mouth Ceremony during which he would touch the corpse at various places on the body in order to restore the senses so the deceased could again see, hear," alt="Égypte ancienne momies funérailles amulettes dieux rituels tombes cercueils officiel livre des morts" width="52" height="52" >

Buy now.

Pay later.

Earn rewards

Representative APR: 29.9% (variable)

Credit subject to status. Terms apply.

Missed payments may affect your credit score

FrasersPlus

Available Products

SIMILAR ITEMS

- Égypte ancienne momies funérailles amulettes dieux rituels tombes cercueils livre des morts

- Hoodie Pour Enfant Avec Un Poulpe Coloré De La Vie Marine

- Boucles d'oreilles cristal Swarovski Megan clair de lune argent tige titane

- FJ France SNCF AUTORAIL HO voie plastique TEE TRAIN à piles MIB`60 RARE !

- Bouteille vase prunus porcelaine pastel chinoise marquée 14" motif oiseau grue lotus

- Marque BambooMN - Mini panier décoratif tissé bambou 2" lots de 30/100/ 1000

- Papier peint 3D Ocean Dark Clouds ZHUB3432 amovible auto-adhésif Ann

- NOUVEAU CADRE DE LUNETTES AUTHENTIQUE CHOPARD SCH273S 0GGH avec miroir clip-on

- Kit de conversion dembrayage volant moteur double à solide pour VW VENTO 1H2 1.9D 96 à 97 AFN

- A.P.C. Sac bandoulière marine femmes poignée supérieure épaule sac à main original limité AP