Vases figurines noir peintre officiel grenier Athènes Grèce Amasis 600 avant JC tasses amphores 362 pix

Vases figurines noir peintre officiel grenier Athènes Grèce Amasis 600 avant JC tasses amphores 362 pix, Vases figurines noir peintre grenier Athènes Grèce Amasis 600 avant JC tasses amphores 362 pix bien

SKU: 827704

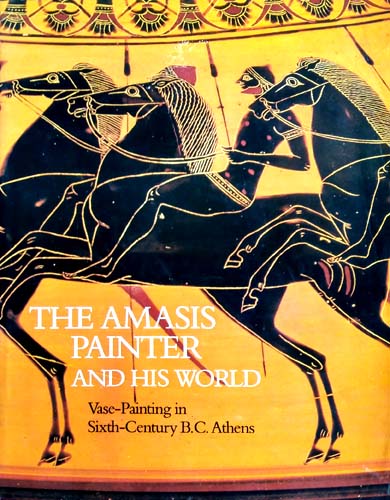

"The Amasis Painter and His World: Vase-Painting in Sixth Century B.C. Athens" by Dietrich von Bothmer.

NOTE: We have 75,000 books in our library, almost 10,000 different titles. Odds are we have other copies of this same title in varying conditions, some less expensive, some better condition. We might also have different editions as well (some paperback, some hardcover, oftentimes international editions). If you don’t see what you want, please contact us and ask. We’re happy to send you a summary of the differing conditions and prices we may have for the same title.

DESCRIPTION: Oversized hardcover with dustjacket. Publisher: J. Barnes & Noble (1985). Pages: 248. Size: Size: 10½ x 8½ x 1 inch; 2½ pounds. Summary: The Amasis Painter was one of ancient Greece’s greatest vase painters, yet his own name has not been recorded, and he is known today only by the name of the potter whose works he most often decorated. A true individualist in the history of Athenian painting, he produced work distinguished by its delicacy, precision, and wit.

When the Amasis Painter began his artistic career around 560 B.C., Attic black-figure vase-painting was already fully established and about to overtake Corinthian pottery in the competition for the Etruscan market. Toward the end of his extraordinarily long career—around 515 B.C., the red-figure technique had been invented and was rapidly supplanting black-figure in fashion. By tracing the Amasis Painter’s stylistic development from his earliest vases to his latest, this book offers a survey of Attic black-figure technique at the peak of its perfection.

The book was prepared to accompany an exhibition held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Toledo Museum of Art, and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 1985-1986. The exhibition is the first ever to be devoted to the work of a single artist from ancient Greece, and twenty-two museums and private collectors have lent the vases on display.

CONDITION: LIKE NEW. Very large unread hardcover w/dustjacket. Thames & Hudson (1985) 248 pages. Book is in unread and new condition in every respect EXCEPT that the dustjacket evidences modest edge and corner shelfwear (as described in greater detail below). From the inside the book is pristine. The pages are clean, crisp, unmarked, unmutilated, tightly bound, and unread, though I would hasten to add that of course it is always possible that the book was flipped through a few times while in the bookstore by bookstore browsing "lookie-loos". However there is absolutely no indications of the book being read. From the outside the dustjacket does evidence modest edge and corner shelfwear. Large, heavy books like this are awkward to handle and so tend to get dragged across and bumped into book shelves as they are shelved and re-shelved. So it is not uncommon to see accelerated edge and corner shelfwear the dustjacket and even the covers of such huge, heavy books. In this instance the edgewear is principally to the dustjacket spine head and hel where there is some mildly abrasive rubbing. Then if you hold the book up to a light source and scrutinize it intently (yeah, were nitpicking at this point), you can see some faint edge crinkling along the open edges of the dustjacket (both front and back sides, top and bottom edges), moreso to the top open edges than the bottom open edges. Its very faint and not readily discerned. However it is our duty (in the interest of full disclosure) to mention it, regardless of how faint it is. The dustjacket is otherwise without further blemish EXCEPT for the fact that the spine of the dustjacket has light faded from the smoky orange of the front and back sides of the dustjacket, to a dusky pink. This is a common issue with this particular book - almost all copies we have ever seen have had dustjackets with a light-faded spine. Beneath the dustjacket the full cloth covers are without blemish. Except for the mild edge wear to the dustjacket and the slightly light-faded dustjacket spine, the overall condition of the book is consistent with new stock from an open-shelf bookstore environment such as Barnes & Noble or B. Dalton, wherein patrons are permitted to browse open stock and so otherwise "new" books might show mild indications of browsing or minor blemishes caused by shelfwear, attributable simply to the ordeal of constantly being shelved, re-shelved, and shuffled about the bookstore shelves. Satisfaction unconditionally guaranteed. In stock, ready to ship. No disappointments, no excuses. PROMPT SHIPPING! HEAVILY PADDED, DAMAGE-FREE PACKAGING! Selling rare and out-of-print ancient history books on-line since 1997. We accept returns for any reason within 30 days! #7004f.

PLEASE SEE DESCRIPTIONS AND IMAGES BELOW FOR DETAILED REVIEWS AND FOR PAGES OF PICTURES FROM INSIDE OF BOOK.

PLEASE SEE PUBLISHER, PROFESSIONAL, AND READER REVIEWS BELOW.

PUBLISHER REVIEWS:

REVIEW: In the sixth century B.C. Greek artists made great strides toward a better understanding of the human body and its more accurate representation, both in sculpture and in painting. The painted pottery vases made in Athens at this time were a major part of this creative movement. The high quality of Attic clay, the perfection of the glaze, and the genius of the potters and painters all contributed. The Amasis Painter was one of the finest of these artists. He is named after the potter Amasis, whose signature appears on several of the vases painted by him. The Amasis Painter was active for an unusually long time, almost fifty years, and we can watch the progression of his work from the beginning of Peisistratos’ rule, circa 561-560 B.C., to the death of Peisistratos’ son Hipparchos in 514 B.C. The Amasis Painter applied his talents to vases of many different shapes, worked at different scales, from tiny figures on small cases to big pictures on large ones, and delighted in many different subjects taken both from daily life and from the realm of the gods and heroes.

353 duo tone illustrations and 9 color plates demonstrate the wealth of images the Amasis Painter has left us; and even small details to which our attention is drawn are illuminated. Since publication in 1956 of the last monograph on the artist (“The Amasis Painter” by Semni Karouzou). Many more known vases have been attributed to him, and many others have come to light. Not only does this book give a full catalogue of half of his preserved work, exhibited together for the first time, it also serves as an account of the artist brought up to date. In the detailed discussions of the individual entries, comparisons are made with the Amasis Painter’s vases that are not included in the exhibition. The relationship of the painter to his forerunners and contemporaries is examined, ornaments are analyzed, and questions of relative chronology of the various vases are raised.

REVIEW: Dietrich von Bothmer is chairman of the Department of Greek and Roman Art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Alan L. Boegehold is professor of classics at Brown University.

REVIEW: Classicist art historian and vase expert, Metropolitan Museum of Art Curator of Greek and Roman Art. Born to an aristocratic Hanover family, Bothmer worked as a youth for the German-Expressionist artist and sculptor Erich Heckel. His older brother, Bernard von Bothmer joined the Berliner museums in 1932 as an Egyptologist and the younger Bothmer decided on a museum career himself. He studied one year at the Friedrich Wilhelms Universität in Berlin before receiving a Cecil Rhodes Foundation grant to study in Oxford in 1938.

In Oxford he met J. D. Beazley with whom he would study. Bothmer received his diploma in 1939 in Classical Studies. He then made an extended visit to the United States, visiting museums and sending information on classical vases to Beazley, who later incorporated it into his subsequent monographs ("Attic Black-Figure Vase Painters", 1956, and "Attic Red-Figure Vase Painters", second edition, 1963). He studied at the University of California, Berkeley, 1940-1942, under the classicist and vase scholar H. R. W. Smith. Bothmer was a fellow at the University of Chicago for a year in 1942 before returning to Berkeley to complete his Ph.D. in 1944.

Anti-German sentiment running strong, Bothmer joined the U. S. army though not a citizen, and was assigned to the south Pacific theatre. There he was wounded in action--carrying a fellow soldier several miles through enemy lines--and awarded a Bronze Star and Purple Heart for heroic achievement and U. S. citizenship. He was demobilized in 1945. Bothmers brother, who had also come to the United States as curator in Brooklyn, introduced the young Bothmer to curators, among them Gisela Marie Augusta Richter, curator of Greek and Roman objects, who steered him into a postion in her department as a curatorial assistant.

Bothmer remained at the Metropolitan the rest of his career. He established himself in the social New York world, joining the soirées of art benefactor Josephine Porter Boardman Crane (1873-1972) among others. He eventually fell into disagreement with the notoriously anti-archaeologist Met director Francis Henry Taylor. In 1959 Bothmer advanced to Curator. The same year he was elected President of the American committee for the Corpus Vasorum Antiquorum, which he held until 1983. In this capacity, he author two fascicules in the CVA, one for the Boston Museum of Fine Arts and another for the Metropolitan.

In 1965 he was appointed adjunct professor at the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University and awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship the following year. He married the oil heiress (and widow of Marquis Jacques de la Bégassière) Joyce Blaffer (b. 1926), who began making significant donations to the Met. In 1990 Bothmer was awarded the Distinguished Research Curator position at the Metropolitan. The Met named the two principal galleries of Classical pottery the "Bothmer Gallery I" and "Bothmer Gallery II" (financed by his wife) in his honor in 1999.

Over the course of his life, he was awarded honorary doctorates from the universities at Oxford, Trier and Emory, named a Chavalier de la Legion dHonneur and a member of both the Académie française and the Deutsches Archäologisches Institut (DAI). Bothmers brother, Bernard, was an Egyptologist/art historian at New York University. Bothmers career at the Metropolitan was often controversial. In 1967, the museums financial director, Joseph V. Noble and Bothmer announced that a famous bronze horse acquired in 1923 by the museum was a forgery based upon stylistic grounds and gamma ray testing.

The pair made a public announcement and removed the horse from view. However, Carl Bluemel doubted their stylistic findings as did the curator of Greek and Roman Art at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Cornelius Vermeule. When more sophisticated technical tests were later performed, the work was proven to be authentic. Bothmer was also accused that his eagerness to secure excellent pieces for the Museum resulted in rewarding unscrupulous dealers and thieves. In one celebrated case, Bothmer persuaded the museum in 1972 to purchase a single vase, a Greek krater decorated by Euphronios, for the (then) unheard of price of $1 million.

The Met sold much of its coin collection to pay for the acquisition, outraging museum professionals and archaeologists alike. The murky provenance of the vase led many archaeologists to believe it had recently been illegally excavated from an Italian archaeological site, likely Cerveteri. Though Bothmer and Metropolitan Director Thomas Hoving insisted the pot had lain in pieces in a family collection in Beirut, Hoving later admitted in 1993 that the evidence sited for the Beirut collection was never part of the Mets Euphronios krater. The krater was repatriated in 2006.

REVIEW: Dietrich Felix von Bothmer (1918–2009) was a German-born American art historian, who spent six decades as a curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where he developed into the worlds leading specialist in the field of ancient Greek vases. Von Bothmer was born in Eisenach, Germany on October 26, 1918. An ardent opponent of the Nazi dictatorship, von Bothmer attended Berlins Friedrich Wilhelms University and then went to Wadham College, Oxford in 1938 on the final Rhodes Scholarship awarded in Germany. There he worked with Sir John Beazley on his books Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters and Attic Black-Figure Vase-Painters, working collaboratively to group works by identifying the individual craftsmen and workshops that had created each of hundreds of Greek vases. He graduated in 1939 with a major in classical archaeology.

A tour of museums in the United States in 1939 left von Bothmer stuck there with the start of World War II. Due to his strong anti-Nazi sentiments, he refused to return to Germany, and narrowly escaped being sent back to Germany against his will. He earned his doctorate at the University of California, Berkeley in 1944. Though not yet a citizen, in 1943 he volunteered for the United States Army. After 90 days in the U.S. Army, he was sworn in as a U.S. citizen in March, 1944. He served in the Pacific theater of operations, earning a Bronze Star Medal and Purple Heart for a conspicuous act of bravery on August 11, 1944, while serving in the South Pacific, where, despite being wounded himself in the thigh, foot, and arm, he recovered a wounded comrade and carried him back three miles through enemy lines.

Following the completion of his military service, he was hired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1946, and was named as a curator in 1959. By 1973, he was department chairman and he was named in 1990 as distinguished research curator. In 1972, together with the Director, Thomas Hoving, von Bothmer argued in favor of the purchase of the Euphronios krater, a vase used to mix wine with water that dated from the sixth century B.C. They convinced the museums board to purchase the artifact for $1 million, which the museum funded through the sale of its coin collection. The Government of Italy demanded the objects return, citing claims that the vase had been taken illegally from an ancient Etruscan site near Rome. The krater was one of 20 pieces that the museum sent back to Italy in 2008 in exchange for multi-year loans of ancient artifacts that were put on display at the Met, as part of an agreement reached in 2006.

Von Bothmers 1977 exhibit "Thracian Treasures from Bulgaria" covered twenty centuries of Thracian culture, with more than 500 art works dating back to the Copper Age. The 1979 show "Greek Art of the Aegean Islands" included 191 pieces, of which 46 came from the Met and a similar number from the Louvre. The remainder came from several different museums in Greece, including the largest known Cycladic sculpture, dating to 2700 to 2300 B.C., on loan from the National Archaeological Museum, Athens. A 1985 exhibition based on his research, "The Amasis Painter and his World: Vase Painting in Sixth Century B.C. Athens," included 65 works of a single artist who created his pottery 2,500 years before, the first to document the history of the work of a single craftsman from that ancient period as a one-man show.

Von Bothmers numerous published works in the field include the 1957 "Amazons in Greek Art", "Ancient Art From New York Private Collections" and "An Inquiry Into the Forgery of the Etruscan Terracotta Warriors in the Metropolitan Museum of Art" (with Joseph V. Noble), both published in 1961, "Greek Vase Painting: an Introduction" in 1972, his 1985 book "The Amasis Painter and His World: Vase-Painting in Sixth-Century B.C. Athens", his 1991 book "Glories of the Past: Ancient Art from the Shelby White and Leon Levy Collection", and in 1992,"Euphronios, peintre: Actes de la journee detude organisee par lEcole du Louvre et le Departement des antiquites grecques, etrusques de lEcole du Louvre". He also contributed in 1983 to "Wealth of the Ancient World (Hunt Art Collections", to "Development of the Attic Black-Figure" Revised edition (Sather Classical Lectures)" in 1986, and a wide variety of other publications. He took a faculty position in 1965 at the Institute of Fine Arts, the nation’s top-ranked graduate program in art history, according to the National Research Councils 1994 study.

Von Bothmer was the recipient of numerous awards and citations, including a Chevalier de la Légion dhonneur; a member of the Académie française (one of only two Americans to have this honor); an honorary fellow of Wadham College; and several honorary doctorates. Complementing his career as a curator and an academic, he served on the Art Advisory Council of the International Foundation for Art Research (IFAR). A resident of both the Manhattan district of New York City and Oyster Bay, New York, von Bothmer died at age 90 on October 19, 2009, in Manhattan. His brother was the renowned Egyptologist Bernard V. Bothmer, who died in 1993.

TABLE OF CONTENTS:

Director’s Foreword.

Preface.

Abbreviations.

The Time of the Amasis Painter by Alan L. Boegehold.

The World of the Amasis Painter by Dietrich von Bothmer.

Color Plates.

Catalogue.

-Amphorae Panel-Amphorae (Type B).

--Panel-Amphorae (Type A).

--Psykter Neck-Amphora.

--Neck-Amphorae.

-Oinochoai.

--Olpai.

--Oinochoai, Shape III (Choes).

--Oinochoai, Shape I.

-Lekythoi.

--Shoulder Type.

--Sub-Deianeira Shape.

-Aryballos.

-Drinking Vessels.

--Mastoid.

--Cup-Skyphos.

--Band-Cups.

--Lip-Cup.

--Cups of Type A.

--Special Cups, Approximating Type B.

Signatures of Kleophrades, Son of Amasis, on Two Cups in the Getty Museum.

Shapes of Vases Painted by the Amasis Painter.

Tripod-Pyxis from the Sanctuary of Aphaia on Aegina by Martha Ohly-Dumm.

PROFESSIONAL REVIEWS:

REVIEW: Greek vase painting is a subject of undisputed artistic importance that has rarely inspired passion outside the academic world. "The Amasis Painter and His World: Vase-Painting in Sixth-Century B.C. Athens" at the Metropolitan Museum of Art is an original idea and a rich subject. Many of these black-figure pots are wonderful...The period covered by the show is one of the most fascinating in Greek art. It is that point where delight in the human body and movement began to wrestle against rigid geometrical order and stylization. The style of contemporaneous Kouroi is very similar to the style of the vase figures.

"The Amasis Painter and His World" is believed to be the first one-man show on an artist from the ancient world. Very little is known about him. There are no absolute dates and only 11 sure signatures. The 65 pots or fragments of pots in the show - covering his entire career in Athens, from around 560 to 515 B.C. - constitute roughly half his known work. As impressive as the accumulation of scholarship has been, Dietrich von Bothmer, the chairman of the Mets department of Greek and Roman art, points out in his catalogue essay that every new attribution still forces a re-examination of everything the artist did.

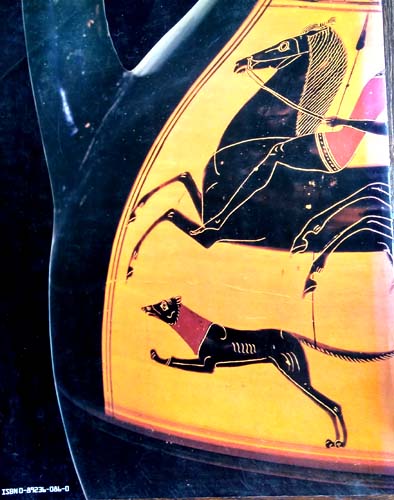

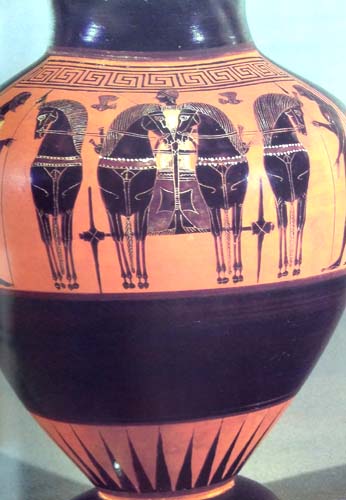

The technique the Amasis painter used is black-figure. Through a three-stage oxidation-reduction process, black forms were created on a reddish-orange ground. His artistic style is neat, precise and filled with the compositional intelligence that is evident in sixth-century architectural sculpture and the kind of elegant, hypnotic, linear rhythms that can also be found in Egpytian hieroglpyhs and reliefs. Mr. von Bothmer writes that the artist was distinguished by his "ability to work at different scales" and by his extreme conservatism. He "repeated himself not because he was devoid of new ideas but because he liked his way of drawing".

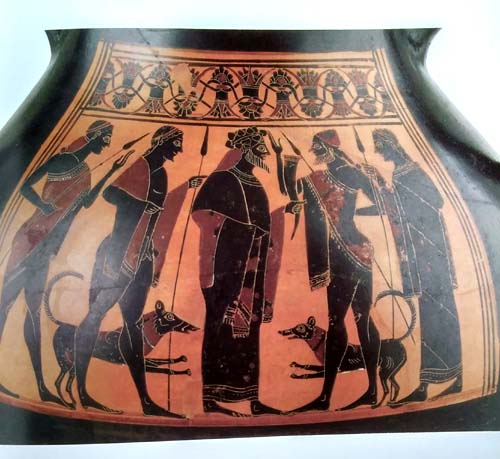

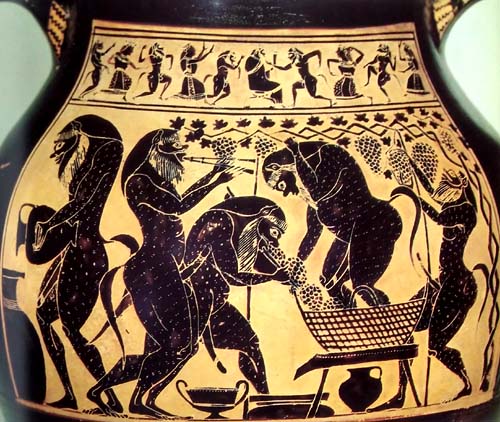

The paintings may be serious, bawdy or humorous. There are images of combat and hunting. There is a friezelike wedding procession and scenes from mythology that reveal how near and yet how far the Greeks thought their gods were. We see Artemis, mistress of wild beasts, in whose hands lions turned into pussycats, standing in the midst of young men from whom she seems as removed as the Virgin Mary on her throne. Perhaps no god appears more often than Dionysus. Greek pots stored, carried and poured wine, and the paintings on them relate all the activities wine inspired and served.

Mr. von Bothmer gives a clue to the power of the works when he writes that the "Amasis painter, more than others, consistently paid attention to the harmony between potted shape and decoration". The images tend to reinforce the circular movement and the fixed presence of the pots in a way that makes them statements about freedom and fate. When there is a sense of movement created by horses or running men, it is modified by the way they seem squeezed into their pictorial bands, and it is often finally stopped by movement going in the opposite direction.

In one painting a warrior taking leave moves right and faces left. The figures to his right face left; the figures to his left face right. As a result of these spatial collisions, the painting shifts between profile and frontal points of view. The movements within the painting strengthen the spatial tension built into the pot itself, turning the whole into a sculptural object that seems so taut that it could explode. The exhibition was organized by the Toledo Museum of Art, with the Metropolitan Museum, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the J. Paul Getty Museum, which published the catalogue. After leaving the Metropolitan the show will travel to Toledo and Los Angeles. [New York Times].

REVIEW: For 2,500 years, we are told, the Amasis Painter never had a one-man show. Now that oversight has been corrected by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in "The Amasis Painter and his World: Vase Painting in Sixth Century B.C. Athens", a retrospective, comprising 65 skillfully decorated black-figure Greek vases and fragments, dating from 560 to 515 B.C. The museum describes the show, remaining through Oct. 27, as the largest exhibition of terracotta vessels by a single ancient Greek artist and the first to document the evolution of one artisans oevre.

This extraordinary exhibition would have been virtually impossible in its day and most unlikely until now, according to Dietrich von Bothmer, chairman of the museums department of Greek and Roman Art, who conceived the show. He contends in its catalogue, published by Thames & Hudson ($60 hardcover, $22.50 paperback), that in ancient Athens, vases by master artists were sold as they emerged from the kiln and were then shipped to distant lands. Most of these jugs, cups and storage vessels did not surface again until they were excavated in the 18th and 19th centuries. The works on view have been assembled from 18 museums and four collectors in Europe and the United States, a feat unheard of until recently when such international shows became acceptable practice.

What we see in this assemblage of highly refined, exquisitely detailed vases and fragments may prove most rewarding to visitors who are not distracted by the weightier Renaissance and Baroque artworks that fill the Blumenthal Patio where the show is held. An awesome energy is captured in the narrative images on these painted pots - warriors, spears in hand, display their heroism with muscular pride; gods, wrapped imposingly in regal robes, greet mortals in realistic settings, and satyrs in erotic and wicked poses cavort wildly at great feasts.

By the time the Amasis Painter began embellishing vases about 560 B.C., vase painters had abandoned purely decorative motifs and learned from the poets - rendering visually the stories from Greek mythology that the public had come to know orally. The technique of black-figure painting was well advanced, as can be seen in these athletically alive figures, depicted as glossy black silhouettes. By then too, details were being executed as light on dark incisions, and opaque ceramic colors - red and white - relieved the chromatic monotony.

It probably matters little that we do not know the name of the artist responsible for these works on which wide-eyed men wrestle, fierce gods are at war and a musician playing two flutes appears to hypnotize an ivy-bearing listener. What has been determined is that 12 vases signed by the potter Amasis - each inscribed "Amasis made me" - were decorated by a craftsman now identified as the Amasis Painter.Much of the research on Amasis is attributed to J. D. Beazley, a British archeologist and scholar of Attic painting, who identified 116 works by this artist in two of his books - "Attic Black-Figure Vase-Painters" published in 1956, and "Paralipomena", in 1971. Since then, 16 more vases by the Amasis Painter have surfaced or been recognized, and about half of the total are in this show. Scholars continue to study Greek vases to find additional works by the man known as the Amasis Painter, as well as others. Because signatures on vases are of potters, not painters, unless a vase with the painters signature appears, his actual name may never be known.

"Was he a nearsighted man?" Mr. von Bothmer wondered aloud during a recent interview. This painter must have been, he said, considering his long career - 45 years - executing such precise images. Mr. von Bothmer explained that the black and red colors on these vessels did not appear until after the pots were fired, which meant, he added that the artist etched his drawing in clay without the aid of contrasting color. Alan L. Boegehold, professor of classics at Brown University, brings 6th century Athens alive in another catalogue essay.

He tells us that Greek potters probably were citizens, who, according to Plato, were not too poor - they bought their own tools and equipment - nor too rich either - they worked long and hard. The exhibition was organized by the Toledo Museum of Art, with the Metropolitan Museum, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the J. Paul Getty Museum, which financed and produced the catalgue. After it closes in New York, the show will travel to Toledo and Los Angeles.

Greek vases have been collected enthusiastically since they first appeared in antiquity. Today, knowledgeable buyers find works of major worth at prices that are far from steep. The Metropolitan Museums wine jug with trefoil mouth depicting warriors bearing shields in the exhibition was purchased by Mr. von Bothmer in a Sothebys auction in 1978 for $5,000. The jug, described by Sothebys as an Attic black-figure vessel from 540 B.C., has since been further identified by Mr. von Bothmer as the work of the Amasis Painter. Other vases by anonymous painters of this period sell for $5,000 or less, the auction house reports.

Major collections of Greek vases usually command higher prices, especially when the vessels offered have been more fully identified. This was the case of the Castle Ashby collection, assembled in the 1820s by the second Marquess of Northampton, and sold in 1980 by the sixth Marquess at Christies in London. In it, the Northampton vase - a red clay vase with black Triton figures from about 540 B.C. - sold for $493,240, a record auction price for a Greek vase, to an unidentified buyer. A two-handled black amphora vase from 550 B.C. by the Amasis Painter sold for $129,800. Two other vases sold for more - a black-bodied amphora depicting Dionysius, dancing satyrs and a horse-drawn chariot brought $415,360 and another vase by a painter known as Elbows Out - so-named because his works invariably show dancers and walking figures with their arms out and in motion - sold for $233,640. [New York Times].

READER REVIEWS:

REVIEW: A remarkably thorough and engrossing catalogue. This is the source of information pertaining to “The Amasis Painter”. An exceptional literary effort. The color plates are phenomenal.

ADDITIONAL BACKGROUND:

REVIEW: The Amasis Painter (active around 550–510 B.C. in Athens) was an ancient Greek vase painter who worked in the black-figure technique. He owes his name to the signature of the potter Amasis ("Amasis made me"), who signed 12 works painted by the same hand. At the time of the exhibition, "The Amasis Painter and His World" (1985), 132 vases had been attributed to this artist. As with any of the artisans working during the sixth century B.C., very little is understood about the Amasis Painters life or personality.

Scholars do know that Amasis is a Greek version of an Egyptian name, more specifically of a contemporary Egyptian king, leading some to believe that the Amasis Painter—or at least the potter Amasis—may have been a foreigner, originally from Egypt. Other possibilities include that he was an Athenian with an Egyptian name, which is highly plausible, given close trade relations between Greece and Egypt, or that his signed name was a nickname given to him by his contemporaries due to some Egyptian characteristic, an example being the alabastron shape.

Exekias’s use of the label “Amasos” for an illustration of an Ethiopian has no clear explanation, but he is generally thought to have been poking fun at Amasis as a contemporary professional rival. Despite the possibility of his Egyptian origin, it is generally agreed by scholars that the Amasis Painter learned his trade in Athens, most likely with the Heidelberg Painter. This painter worked around 525–550 B.C., and is best known for his work on Siana cups.

The Amasis Painter borrows scenes from the Heidelberg Painter, such as a warrior dressing himself in greaves with multiple bystanders; however, the Amasis Painter adds his own touch in the treatment of his figures, imparting a greater sense of detail, and often adding a signature double-band border and palmette-lotus festoon to the ornamental decoration. In other examples, the Amasis Painter’s use of fringed garments also emphasizes a possible close relationship between the two.

The career of the Amasis Painter was long, spanning nearly 50 years from around 560 to 515 B.C., and encompassed the transition from the early to mature phases in Attic black-figure vase painting.[9] The Amasis Painter was singular in his reaction to the rapid changes happening around him. His style, while generally conservative, evolved with certain developments in the medium. However, the Amasis Painter also rejected certain trends and managed to maintain a consistency that can be traced throughout, making it difficult to date works within his lifetime.

His development over the course of his career, which is loosely classified into early, middle and late phases, demonstrates the artist’s journey from novice to master. As R. M. Cook explains, "His early work is conventional and tame, but as he matures he displays a more individual assurance". There are 11 black figure vases and one fragment that are painted by the same hand and bear a signature that reads, Amasis mepoiesen meaning "Amasis made me", indicating the artist Amasis as the potter of these works.

As all 12 works were decorated by a single painter, some scholars have assumed that the potter and painter were one in the same. However, since the 1971 attribution of a signed work by Amasis to the hand of the Taleides Painter, connoisseurs are reminded to distinguish between the potter Amasis and the Amasis Painter with care. The painters 12 signed pieces include three broad-shouldered neck-amphorae, four olpai (an early form of wine jug), one band cup, one cup, one small bowl, a pyxis and a vessel fragment.

For scholars who believe that the potter and painter were identical, the petite and refined shapes of the Amasis vessels reinforce the argument for Amasis innovative contributions to sixth-century Athenian vases. As Boardman writes, "The potting of the Amasis Painters vases is as distinctive as the painting. The concurrence of the two phenomena might well suggest that potter and painter were one man, particularly as the distinctive elements in each craft seem to share a common spirit."

Whether the painter was indeed the potter or not, the Amasis Painter decorated a wide variety of shapes, including panel and neck amphorae, used for wine or oil storage; oinochoai, wine pouring jugs; lethythoi, oil jars; alabastra and aryballoi, for oils or perfumes; and a variety of drinking cups, including mastoids, skyphoi, and kylikes. Of these shapes, the Amasis Painter seems to have preferred smaller, "user-friendly" forms, from 30 to 35 centimeters high, and reduced dimensions of painting space, for example, in panels.

The Amasis Painter tackled nearly every subject available to the sixth-century vase painter; of 165 scenes, 20 are narrative mythological subjects. However, his true character as an artist and most important contributions to the legacy of black-figure painting are revealed in his non-narrative subjects of gods and mortals, and in his many genre scenes. The Amasis Painter is credited as the first to show non-specific scenes of interactions between gods, especially Dionysus and his merry revelers whom he painted more than 20 times, compared to Exekias’ one.

Another of his most common subjects is Athena facing Poseidon, and while the viewer is reminded of the myth of the competition for Athens, the Amasis Painter’s portrayal of this scene typically does not convey a specific narrative. He extends these representations of gods to include mortals; as Stewart argues, such scenes speak to the painters ability to evoke a contemporary cultural awareness of the ever-present gods in Greek daily life. Departure from the traditional canon allowed the Amasis Painter greater freedom to explore particularized detail in his treatment of mythological subjects.

The Amasis Painter was also a pioneer in his depiction of genre scenes of everyday life, such as the transport by cart of a newly married couple to the house of the groom, or the working of wool by a group of women. The Amasis Painter is recognizable by his preference for symmetry, precision and clarity, and expressiveness through mastery of his medium and composition. As Von Bothmer points out, the artist is especially strong as a miniaturist, and highly skilled in his creation of harmony between shape and decoration.

Another unique characteristic of the Amasis Painters style is his occasional use of a glaze outline to delineate womens figures, specifically maenads. While he was not the first to use a glaze outline, he was the first to combine it with the black-figure technique on a single vessel, possibly anticipating the red-figure style, as Semni Karouzou suggests, or reacting to it. The extent of the Amasis Painters interaction with the red-figure technique, which was in use at the end of his career, is unknown, but the free, curvilinear lines and bright compositions in his later work may indicate its influence.

Connoisseurs are also able to identify the work of the Amasis Painter by his characteristic use of ornament. The artist typically reinforced his frames with a double and sometimes triple glazed line, another carryover from the Heidelberg Painter. In addition, he might use this double or triple line to separate the panel scene from the ornamental band, and occasionally used a meander. Two other motifs he regularly employed in were zig-zag bands and rosettes. Finally, the Amasis Painter is most recognizable in his use of floral ornamental bands, which Beazley characterizes as lively and vivid.

Beginning with simple upright-buds, as opposed to the pendant buds characteristic of other artists, he eventually developed the more complex palmette-lotus festoon. He used both of these motifs throughout his career, and, especially in later works, they are notable for their excellent symmetry and balance of color. As Mertens describes, “In the palmette-lotus festoon…, each unit is meticulously spaced within the field, and extraordinary care has been taken with the tendrils, especially those developing from the palmettes. The intervals are as important as the forms.”

The Amasis Painter and Exekias are traditionally considered by scholars to represent the two "schools" of Attic black-figure painting in the mid-6th century B.C., and are credited with carrying the black-figure technique to full maturity; traditional scholarly discussion of either painter implies a comparison. Both artists were exceptional draughtsmen and masters of detail, which was employed to convey a vivid scene.

In the traditional literature, scholars have favored Exekias as the superior artist, and he is credited with mastering the pre-Classical development of narrative: condensing well-known stories and depicting moments that imply past and future events, and “invoking causes and consequences with a power and economy unattained by his predecessors.” Art historians credit the Amasis Painter, on the other hand, with the development of original, non-narrative genre scenes. They consider his strongest work to be examples that employ humor, wit and expression through masterful use of both the graver and the brush.

In the prevailing literature prior to the Getty exhibition, the Amasis Painter was considered an outlier in an Exekian march towards classicism. The Amasis Painter and His World, however, served to reintroduce the Amasis Painter in a new light: as one crucial thread in a network of painters in sixth-century Greece. Importantly, J. D. Beazleys connoisseurship accounts for the oeuvre of the Amasis Painter, and allows modern viewers and scholars to consider his work in this way. Exekias and the Amasis Painter were equally talented, each in his own way, and instrumental to the development of black-figure vase painting in Athens.

In autumn of 1985, "The Amasis Painter and His World", the first retrospective of an Attic black-figure artist, opened at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Curated by Dr. Dietrich von Bothmer, J. D. Beazleys close friend and associate, the show brought together 65 works attributed to the Amasis Painter from around the world, opening on the centenary of Beazleys birth. Beazley devoted his 60-year career to diligent observation and detailed categorization and attribution of ancient Greek vase painters and schools based on style.

The exhibition recognized not only the work of the Amasis Painter, but also Beazleys scholarship, which established this artists body of work. The scholarly catalogue for exhibition and the papers published from the accompanying colloquium greatly contributed to an awareness of and scholarship on this painter, and helped to relocate him within the complex tapestry of artists and influence of sixth-century black-figure vase painting.

"The Amasis Painter and His World" was a critical step in acknowledging the individual body of work of this painter and his contributions to the black-figure repertoire, while also highlighting the limitations of over- or under-estimating the influence of a single artist working in any age. Beazleys legacy speaks to this in his attributions to artists and schools regardless of perceived quality. The ability to view the Amasis Painters large body of work in a single exhibition has led to a better appreciation of the context of his workshop—and the hundreds of other black-figure vases by the many painters and potters working in the sixth-century B.C. The Amasis Painters oeuvre provides a fascinating glimpse into one part of this puzzle, which, when pieced together by scholars, reveals much about the arts and crafts of Archaic Greece. [Wikipedia].

REVIEW: We know the names of some potters and painters of Greek vases because they signed their work. Generally a painter signed his name followed by some form of the verb painted, while a potter (or perhaps the painter writing for him) signed his name with made. Sometimes the same person might both pot and paint: Exekias and Epiktetos, for example, sign as both potter and painter. At other times potter and painter were different people and one or both of them signed. However, not all painters or potters signed all their work. Some seem never to have signed their vases, unless by chance signed pieces by these craftsmen have not survived.

Even in the case of unsigned vases, it is sometimes possible, through close examination of minute details of style, to recognize pieces by the same artist. The attribution of unsigned Athenian black- and red-figured vases to both named and anonymous painters was pioneered in the twentieth century by Sir John Davidson Beazley. Other scholars have developed similar systems for other groups of vases, most notably Professor A.D. Trendall for South Italian red-figured wares. For ease of reference Beazley and the others gave various nick-names to the anonymous painters whom they identified.

Some are called after the known potters with whom they seem to have collaborated - the Brygos and Sotades Painters, for example, are named from the potters of those names. Other painters are named from the find-spot or current location of a key vase, such as the Lipari or Berlin Painters. A few, such as the Burgon Painter, take their names from former or current owners of key vases. Others are named from the subjects of key vases, such as the Niobid, Siren or Cyclops Painters, or else from peculiarities of style, such as The Affecter or Elbows Out Painters. [British Museum]

REVIEW: Ancient Greek black-figure pottery (named after the color of the depictions on the pottery) was first produced in Corinth, circa 700 B.C., and then adopted by pottery painters in Attica, where it would become the dominant decorative style from 625 B.C. and allow Athens to dominate the Mediterranean pottery market for the next 150 years. Laconia was a third, albeit minor, producer of the style in the first half of the 6th century B.C. The more than 20,000 surviving black figure vessels make it possible not only to identify artists and studios, but they also provide the oldest and most diverse representations of Greek mythology, religious, social, and sporting practices. The pottery vessels are also an important tool in determining the chronology of ancient Greece.

Evolving from the earlier geometric designs on pottery, the black-figure technique depicted animals (more favored in Corinth) and human silhouette figures (preferred in Athens) in naturalistic detail. Before firing, a brilliant black pigment of potash, iron clay, and vinegar (as a fixative) was thickly applied to vases and gave a slight relief effect. Additional details such as muscles and hair were added to the figures using a sharp instrument to incise through the black to reveal the clay vessel beneath and by adding touches of red and white paint. Vessel borders and edges were often decorated with floral, lotus, and palmette designs.

Certain color conventions were adopted such as white for female flesh, black for male. Other conventions were an almond shape for women’s eyes, circular for males, children are as adults but on a smaller scale, young men are beardless, old men have white hair and sometimes stoop, and older women are fuller-figured. Some gestures also became conventional such as the hand to the head to represent grief. Another striking feature of the style is the lack of literal naturalism. Figures are often depicted with a profile face and frontal body, and runners are in the impossible position of both left (or right) arms and legs moving forward. There was, however, some attempt at achieving perspective, frontal views of horses and chariots being especially popular.

Typical vessels of the style are amphorae, lekythoi (handled bottles), kylixes (stemmed drinking cups), plain cups, pyxides (lidded boxes), and bowls. Painters and potters were usually, although not always, separate specialists. The first signed vase was by Sophilos and dates to circa 570 B.C. Many other individual painters have been identified with certainty through their signatures (most commonly as ‘...made this’) and many more unsigned artists may be recognized through their particular style.

Perhaps the most celebrated example of the technique is the Francois Vase, a large volute krater, by Kleitias (circa 570 B.C.) which is 66 cm high and covered in 270 human and animal figures depicting an astonishing range of scenes and characters from Greek mythology including, amongst others, the Olympian gods, centaurs, Achilles, and Peleus.

The technique would eventually be replaced by the red-figure (reverse) technique around 530 B.C. The two styles were parallel for some time and there are even ‘bilingual’ examples of vases with both styles, but the red-figure, with its attempt to more realistically portray the human figure, would eventually become the favored style of Greek pottery decoration. [Ancient History Encyclopedia].

REVIEW: Black-figure pottery painting, also known as the black-figure style or black-figure ceramic is one of the styles of painting on antique Greek vases. It was especially common between the 7th and 5th centuries B.C., although there are specimens dating as late as the 2nd century B.C. Stylistically it can be distinguished from the preceding orientalizing period and the subsequent red-figure pottery style. Figures and ornaments were painted on the body of the vessel using shapes and colors reminiscent of silhouettes. Delicate contours were incised into the paint before firing, and details could be reinforced and highlighted with opaque colors, usually white and red.

The principal centers for this style were initially the commercial hub Corinth, and later Athens. Other important production sites are known to have been in Laconia, Boeotia, eastern Greece, and Italy. Particularly in Italy individual styles developed which were at least in part intended for the Etruscan market. Greek black-figure vases were very popular with the Etruscans, as is evident from frequent imports. Greek artists created customized goods for the Etruscan market which differed in form and decor from their normal products. The Etruscans also developed their own black-figure ceramic industry oriented on Greek models.

Black-figure painting on vases was the first art style to give rise to a significant number of identifiable artists. Some are known by their true names, others only by the pragmatic names they were given in the scientific literature. Especially Attica was the home of well-known artists. Some potters introduced a variety of innovations which frequently influenced the work of the painters; sometimes it was the painters who inspired the potters’ originality. Red-figure as well as black-figure vases are one of the most important sources of mythology and iconography, and sometimes also for researching day-to-day ancient Greek life. Since the 19th century at the latest, these vases have been the subject of intensive investigation.

The foundation for pottery painting is the image carrier, in other words the vase onto which an image is painted. Popular shapes alternated with passing fashions. Whereas many recurred after intervals, others were replaced over time. But they all had a common method of manufacture: after the vase was made, it was first dried before being painted. The workshops were under the control of the potters, who as owners of businesses had an elevated social position.

The extent to which potters and painters were identical is uncertain. It is likely that many master potters themselves made their main contribution in the production process as vase painters, while employing additional painters. It is, however, not easy to reconstruct links between potters and painters. In many cases, such as Tleson and the Tleson Painter, Amasis and the Amasis Painter or even Nikosthenes and Painter N, it is impossible to make unambiguous attributions, although in much of the scientific literature these painters and potters are assumed to be the same person. But such attributions can only be made with confidence if the signatures of potter and painter are at hand.

The painters, who were either slaves or craftsmen paid as pottery painters, worked on unfired, leather-dry vases. In the case of black-figure production the subject was painted on the vase with a clay slurry (a glossy slip, in older literature also designated as varnish) which turned black after firing. This was not a "color" in the traditional sense, since this surface slip was of the same material as the vase itself, only differing in the size of the component particles. The area for the figures was first painted with a brush-like implement.

The internal outlines and structural details were incised into the slip so that the underlying clay could be seen through the scratches. Two other earth-based pigments were used to add details—red and white for ornaments, clothing or parts of clothing, hair, animal manes, parts of weapons and other equipment. White was also frequently used to represent women’s skin. The success of all this effort could only be judged after a complicated, three-phase firing process which generated the red color of the vase clay and the black of the applied slip.

Specifically, the vessel was fired in a kiln at a temperature of about 800 °C, with the resultant oxidization turning the vase a reddish-orange color. The temperature was then raised to about 950 °C with the kilns vents closed and green wood added to remove the oxygen. The vessel then turned an overall black. The final stage required the vents to be re-opened to allow oxygen into the kiln, which was allowed to cool down. The vessel then returned to its reddish-orange colour due to renewed oxidization, while the now-sintered painted layer remained the glossy black color which had been created in the second stage.

Although scoring is one of the main stylistic indicators, some pieces do without. For these, the form is technically similar to the orientalizing style, but the image repertoire no longer reflects orientalizing practice. The evolution of black-figure pottery painting is traditionally described in terms of various regional styles and schools. Using Corinth as the hub, there were basic differences in the productions of the individual regions, even if they did influence each other. Especially in Attica, although not exclusively there, the best and most influential artists of their time characterized classical Greek pottery painting.

The black-figure technique was developed around 700 B.C. in Corinth and used for the first time in the early 7th century B.C. by Proto-Corinthian pottery painters, who were still painting in the orientalizing style. The new technique was reminiscent of engraved metal pieces, with the more costly metal tableware being replaced by pottery vases with figures painted on them. A characteristic black-figure style developed before the end of the century. Most orientalizing elements had been given up and there were no ornaments except for dabbed rosettes (the rosettes being formed by an arrangement of small individual dots).

The clay used in Corinth was soft, with a yellow, occasionally green tint. Faulty firing was a matter of course, occurring whenever the complicated firing procedure did not function as desired. The result was often unwanted coloring of the entire vase, or parts of it. After firing, the glossy slip applied to the vase turned dull black. The supplemental red and white colors first appeared in Corinth and then became very common. The painted vessels are usually of small format, seldom higher than 30 cm. Oil flasks (alabastra, aryballos), pyxides, kraters, oenochoes and cups were the most common vessels painted. Sculptured vases were also widespread.

In contrast to Attic vases, inscriptions are rare, and painters’ signatures even more so. Most of the surviving vessels produced in Corinth have been found in Etruria, lower Italy and Sicily. In the 7th and first half of the 6th centuries B.C., Corinthian vase painting dominated the Mediterranean market for ceramics. It is difficult to construct a stylistic sequence for Corinthian vase painting. In contrast to Attic painting, for example, the proportions of the pottery foundation did not evolve much. It is also often difficult to date Corinthian vases; one frequently has to rely on secondary dates, such as the founding of Greek colonies in Italy.

Based on such information an approximate chronology can be drawn up using stylistic comparisons, but it seldom has anywhere near the precision of the dating of Attic vases. Mythological scenes are frequently depicted, especially Heracles and figures relating to the Trojan War. But the imagery on Corinthian vases does not have as wide a thematic range as do later works by Attic painters. Gods are seldom depicted, Dionysus never. But the Theban Cycle was more popular in Corinth than later in Athens. Primarily fights, horsemen and banquets were the most common scenes of daily life, the latter appearing for the first time during the early Corinthian period.

Sport scenes are rare. Scenes with fat-bellied dancers are unique and their meaning is disputed up to the present time. These are drinkers whose bellies and buttocks are padded with pillows and they may represent an early form of Greek comedy. The transitional style (640-625 B.C.) linked the orientalizing (Proto-Corinthian) with the black-figure style. The old animal frieze style of the Proto-Corinthian period had run dry, as did the interest of vase painters in mythological scenes. During this period animal and hybrid creatures were dominant. The index form of the time was the spherical aryballos, which was produced in large numbers and decorated with animal friezes or scenes of daily life.

The image quality is inferior compared with the orientalizing period. The most distinguished artists of the time were the Shambling" alt="Vases figurines noir peintre officiel grenier Athènes Grèce Amasis 600 avant JC tasses amphores 362 pix" width="52" height="52" >

Buy now.

Pay later.

Earn rewards

Representative APR: 29.9% (variable)

Credit subject to status. Terms apply.

Missed payments may affect your credit score

FrasersPlus

Available Products

SIMILAR ITEMS

- Vases figurines noir peintre grenier Athènes Grèce Amasis 600 avant JC tasses amphores 362 pix

- Homme 9.0US Nike Air Jordan 1 Retro High Og Court Violet Blanc/Noir

- Monnaie, France, Jean II le Bon, Gros à la fleur de lis, 1358, TB+, Billon

- AEZ jantes Montréal noir 7.5Jx18 ET50 5x114.3 pour Renault Clio Fluence Latitude

- Robe En Cuir Blanc Réel Pour Femmes En Agneau Doux Longueur Genou Robe Bodycon

- Diagnostic, conceptualisation et planification du traitement pour adultes : une étape par étape

- Réceptacle de porte à ressort neuf Appleton ADR6034 aluminium 60 ampères Powertite ⚡

- KIT DE DURITE SAMCO KTM Y Piece Race Design, KIT 4 PIÈCES, ORANGE, KTM-53 OU

- Sculpture météorite noire culture chinoise Hongshan 12,6" motif humain Zong Cong

- [FURLA] Shoulder Bag BELLA MINI TOP HANDLE Womens AVORIO g (1007-0AV00)